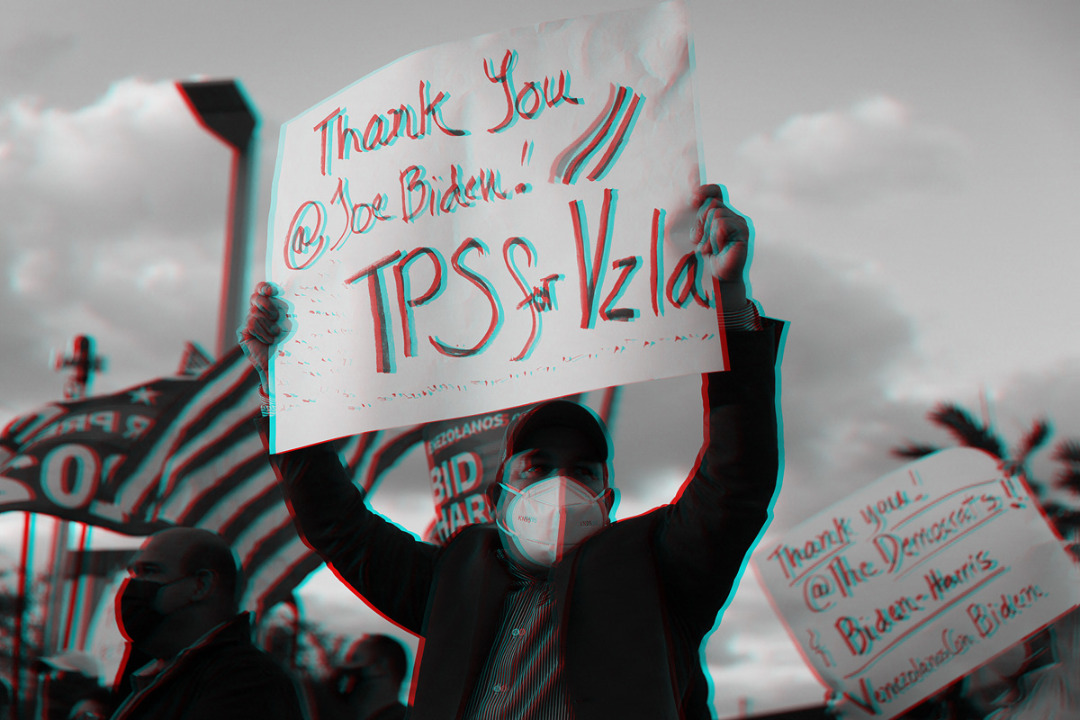

President Joe Biden’s administration announced on 8 March 2021 that the Venezuelan population in the US will be eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS)1. The measure could benefit 380,000 Venezuelans who have been on US soil since 8 March, for a renewable 18-month period. Likewise, the Biden administration announced the renewal of the Executive Order2 that affirms that Venezuela is a threat to the national security of the United States, an order on which the systematic unilateral coercive measures and economic sanctions exercised by the US against Venezuela are based.

The TPS is accompanied by international pressure for “free and fair elections in Venezuela”, an initiative long pushed for by US senators Bob Menéndez and Marco Rubio,3 promoters of Public Law 113-278 (“Law for the Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society in Venezuela”), the legal instrument with which the blockade against Venezuela was formalized in December 2014, and which constitutes the basis for the issuance of the subsequent coercive measures. Therefore, the designation of Venezuela as a beneficiary country for TPS also entails its entry into a list of countries with serious problems, which seeks to strengthen the rhetoric of the ‘failed state’.

Temporary Protected Status has had a great impact on international public opinion, and is often presented as a paradigm in terms of migrants’ human rights, to be followed by all other countries in the hemisphere.

What are Temporary Protection Statuses?

They were created in 1990, through the Immigration Act – Public Law No. 101-648, passed in November of that year, during the administration of George H. W. Bush. It was then that the US began to grant extraordinary leave to migrants from countries deemed by the US government to be suffering from armed conflict or natural disasters. It was originally intended for the war-affected Salvadoran population.

Since 1990, the designation of countries for TPS was made by the Attorney General. However, since 2017 the authority responsible for designating countries is the US Secretary of Homeland Security (currently Alejandro Mayorkas, appointed by Joe Biden).

At present, around 400,000 immigrants in the United States from 10 countries have TPS.4 The group of countries currently designated are: El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Yemen and Venezuela, in any case, in September 2022, the Secretary of Homeland Security will determine whether Venezuela continues to meet the conditions for granting this benefit.5

TPS is not a grant of legal status, let alone US citizenship. Those who access TPS are not necessarily eligible for citizenship, but receive temporary protection from deportation and permission to work in the US for a limited time. The US has the power to terminate TPS, as in fact happened during the Trump administration with the Haitian and Honduran cases.

A permanent demand of migrant communities in the US is that TPS should give way to access to permanent residency, as many of the migrants who have been part of the status have made families in the country and are faced with the dilemma of having to separate once the TPS term ends. In this sense, and contravening the pro-migrant discourse of its electoral campaign, the Biden administration has assumed the same position as the Trump administration, denying more secure access to permanent residency to TPS beneficiaries.6

Legal aspects

From a legal point of view, despite the public speeches made by the Biden administration and its international allies, TPS is not based on the human rights and guarantees enshrined internationally for migrant populations (including asylum seekers and refugees), nor on the concomitant obligations for states (in accordance with the relevant conventions), but on the contrary, is based on the discretionary powers of a host state to “grant” certain transitory benefits to a migrant population assumed to be a temporary “guest”.

What the official discourse conceals is that TPS does not legally lead to legal permanent resident status or US citizenship, nor does it confer any other immigration status. It does not grant the political rights granted to citizens of a country. Furthermore, if the measure is not extended, beneficiaries would revert to their previous immigration status (regular or irregular), and those in irregular status would not have permission to work legally and could easily be deported. Therefore, the Statute excludes beneficiaries from a potential definitive integration, since, although they can stay temporarily, most migrants do not have a visa.

By denying full guarantees of human rights, reserving their exercise only to those who have acquired US citizenship, the enjoyment of social “benefits” (health, education and work) – by the migrant population – is subject to certain limits: the Biden Administration can end them at any time, in the event of a threat to national security or public health.

In this way, it does not guarantee an explicit and unrestricted right to health, education and work, as the US government can decide to limit the TPS in force, suspending them temporarily or permanently, thus creating additional vulnerabilities to those that already exist.

It should also be noted that the “benefits” of TPS will not be exercised immediately7 nor will they benefit the target population automatically; they require a series of conditions that will be assessed and considered in a discretionary manner, taking time to apply them adequately. The key legal-administrative element of TPS is the space available to the U.S. administration to determine its articulation -according to its political objectives- in the face of internal and external conjunctural events (one of which is the externalization of the U.S. border).

On the one hand, “temporary protection” is a kind of subsidiary or complementary protection measure, being restrictive – lacking the scope provided by the established modalities of international protection – given that temporariness (or “provisionally”) implies providing lesser legal benefits than those held by an asylee or a refugee. The TPS granted to the “beneficiaries” contains numerous ambiguities and gives much room for maneuver to the U.S. administration: the granting of permits is optional, it allows them to condition the scope and implementation of international protection, without apparently violating international law.

On the other hand, the Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelan migrants establishes exceptions: it can only be requested by those who have entered the U.S. before March 8, 2021, that is, it is exclusive for persons already continuously physically present (CPP) or in continuous residence (CR)8 in the U.S. territory, as long as they can prove that they have been residing in the U.S. before that date.9 Venezuelans have 180 days to apply for this program.

In order to benefit from TPS, they must be considered eligible after a security review, for which they must demonstrate that they do not have a criminal record, including criminal or security-related grounds (for which there is no exemption), as well as pay fees to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) of US$50 for children under 14, US$50 to file the form, US$80 for biometric records costs, and US$410 to apply for a work permit.

The statute allows an exception to the continuous physical presence requirement and the continuous residency requirement for short, casual, and innocent departures outside the United States. When the individual applies for or re-registers for TPS, he or she must inform USCIS of all absences from the United States. USCIS will determine whether the exception applies in each case10. For this reason, one of the unstated objectives of TPS is to regulate freedom of movement, strictly controlling the movement of migrants, in order to curb their transit migration.

However, in the public discourse of the Biden Administration and its international allies, the express intention of TPS is to guarantee human rights to groups of migrants who have been officially characterized as people “fleeing massively and desperately from the persecutions and violations against them”, which would give them the legal status of asylum seekers and refugees. However, the Statute contradicts such intention, being oriented to discourage the request for its recognition.

According to estimates offered in April 2020 by UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration, more than 351,114 Venezuelans are in the United States11 seeking relief from the “humanitarian crisis”, of which -according to the White House- 323,000 will benefit from TPS12 (for a period of 18 months, extendable), allowing 200,000 of them to receive temporary work permits, as well as protection against deportation. Venezuelan migrants, according to data from international agencies, have been among the largest applicants for affirmative asylum, that is, those who enter the country legally. More than 74,000 Venezuelans have sought asylum in the United States over the past four years, of which only 13,300 Venezuelans have received asylum. During Donald Trump’s administration, almost 4,200 Venezuelans were deported, with 2019 being the year that registered the highest number (with 1,619)13. In relation to such deportations, as an immediate antecedent of the TPS, former President Donald Trump approved in January of this year an Executive Order, which only proposed to postpone the expulsion by deportation for the following 18 months.

The legal character of TPS is based on its “charitable” approach, which does not really guarantee human rights: the public discourse of the US government regarding the benefits of TPS is based on the one that seeks to protect “their persecuted brothers”, based on “American generosity” a supposed global “moral responsibility”, instead of being based on a real and concrete commitment to the guarantees of human rights established in the existing conventions on the migrant population. Indeed, the United States tops the list of countries that have neither signed nor ratified the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (CMW) or its Optional Protocol.14

The discourse of charitable aid does not deal with formally recognized rights (nor with their effective exercise or protection), but is based on circumstantial and revocable privileges, and therefore contradicts any approach to guaranteeing human rights. The instrumentalization of this discourse points to a complementarity between temporary protection regimes and strategies based on charitable assistance rather than on the guarantee of rights, and on temporariness (transitory presence) rather than on citizenship (or nationalization).

TPS enshrines a volatility in the legal status of migrants: as a temporary “benefit” – and not a guarantee’s regime– it leads to the violation of international refugee law: deportations can be ordered and can be carried out without recourse to due guardianship by a competent judge. Moreover, this Statute does not guarantee legal certainty for so-called “asylum seekers and refugees”, since it does not stipulate their rights or any recourse (neither administrative nor judicial), and does not allow them to assert them before any court.

Although it establishes the obligation of irregular migrants to register with the competent authority (Department of Homeland Security), it does not consider the number of people who may decide not to register for fear of being criminalized and deported. Since TPS itself recognizes that the majority of migrants are in an irregular situation, the optional and discretionary nature of the protection measures is a way of facilitating the conversion of exceptions into the rule.

On the other hand, the fact that the Statute is to benefit Venezuelan migrants is an unusual exclusion of identical policies for migrants of other nationalities (and even possible refugees and asylum seekers) with presence in U.S. territory, evidencing a suspicious discriminatory -and unequal- treatment towards other “urgent” migrant populations.15

Political Aspects

The current implementation of TPS in favor of Venezuelan migrants is a strategy to cover up the devastating effects of unilateral sanctions on Venezuela, in order to distract public opinion from the public denunciations made at the beginning of February by the UN Special Rapporteur on unilateral coercive measures, Alena Douhan.

Indeed, the current U.S. Secretary of State, Antony John Blinken, said he “feels committed to the compatriots of Venezuela who are in its territory”, however, his country renewed the illegal measures that have violated for years the fundamental rights of the Venezuelan people: President Joe Biden extended on March 2 the Executive Order 13.692, which declares Venezuela as “an unusual and extraordinary threat”, thus widening the way to increase coercive measures and the economic blockade, actions that affect the human rights of all Venezuelans as revealed in the report presented by the Special Rapporteur.

Since the economic and social difficulties that Venezuela is currently facing are a direct and calculated consequence of the scheme of unilateral and arbitrary sanctions applied against the country during the last seven years, the most coherent action of the U.S. government should be the total and immediate lifting of the unilateral coercive measures that have caused inhuman suffering to all the Venezuelan people, given the havoc they have caused to the economy of that country.

Based on the internal political context of the United States, it has been assured that the TPS is an electioneering gesture by President Biden,16 in order to obtain the support of the voters of the state of Florida, which was key for the presidential elections and also for the mid-term elections to be held in 2022.

In the regional geopolitical context of the United States, one function of the TPS is to contribute to the repositioning of the United States as a hegemonic actor -and of President Biden as “hemispheric leader”- in the strategy to depose the Venezuelan government, bringing together under such leadership its allies in Latin America and Western Europe, and discursively exalting its role as protector of a “people persecuted by a dictatorship”. The attitude expressed by Latin American and Caribbean governments confirms the existence of a shared agenda, characterized by a change of discourse regarding Venezuelan migration, as well as the approval of similar temporary protection measures (case of Colombia), acceptance of expired passports (in the Dominican Republic and Brazil, among others) and the generation of employment programs for the Venezuelan population (Guyana).

Biden intends to renew U.S. leadership towards Latin American and Caribbean countries by appealing to an apparent “shift in the immigration agenda”,17 in an attempt to renew its world leadership. The fact that this is being emulated by other countries reveals that these are coordinated actions. Biden intends to set himself up as the actor capable of managing the regional crisis that Central and South American (including Venezuelan) migration supposedly represents, by coordinating efforts among countries in the region and mobilizing the support and resources of the international community.

This type of “protective” policies -based on the “concession” of provisional benefits- are contrary to the guarantee of rights. Thus, according to the World Bank: “integrating refugee support into the mainstream of government service provision may be more cost-effective than setting up large-scale camps”.18 This way, the emphasis is on temporary stay, rather than guaranteeing rights.

It is based on the premise that the benefited population will eventually “leave”, so that no granting of permanent residence or citizenship (with the resulting rights) is required, thus scamming the legal framework based on human rights (education, health, work) in favor of the migrant population. As a consequence, greater vulnerability is generated.

To conclude, it is necessary to call attention to the need to debate the issue of Venezuelan migration to the United States by unveiling the causes that propitiate it (hemispheric strategies of unconventional warfare, unilateral coercive measures, etc.), intertwined with the secular American project of hemispheric hegemony (and the Monroe Doctrine vis-à-vis the presence of Russia, China and Iran in Latin America), and framed in the reshaping and consolidation of Washington-friendly governments in the continent, within the recolonizing policies of the United States.

These logics of power mold and shape migratory movements, reproducing new and old forms of apartheid under the guise of “democracy”,19 developing currents of “guest workers” (unskilled workers, as cheap temporary labor force) of legal character, but without equal rights, and even generating contradictions between the currents that demand freedom of movement of labor, against the conservative forces that demand immigration control (under securitization schemes).

This whole phenomenon must be contextualized geopolitically within the structural determinants of an asymmetrical system of power, which generates classifying and dividing political strategies of the migrant population (affirming its colonialities), actively shaped by the nations of destination in conjunction with international institutions, under the aegis of the United States.

References

1 https://www.france24.com/es/am%C3%A9rica-latina/20210309-eeuu-venezolanos-estatus-proteccion-temporal

2 https://pdctv.info/biden-renueva-orden-ejecutiva-que-considera-a-venezuela/

4 https://theobjective.com/further/las-claves-del-estatuto-de-proteccion-temporal-para-venezolanos-en-colombia-y-eeuu

5 https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-internacional-56287550

6 https://www.alianzaamericas.org/press-releases/una-vez-mas-la-administracion-de-biden-rompe-la-promesa-de-proteger-a-las-personas-inmigrantes/

7 https://theobjective.com/further/las-claves-del-estatuto-de-proteccion-temporal-para-venezolanos-en-colombia-y-eeuu

8 https://venezuelamigrante.com/featured/tps-para-los-venezolanos-en-estados-unidos/

9 https://www.france24.com/es/am%C3%A9rica-latina/20210309-eeuu-venezolanos-estatus-proteccion-temporal

10 https://venezuelamigrante.com/featured/tps-para-los-venezolanos-en-estados-unidos/

11 https://noticias.com.ve/featured/embajada-de-venezuela-en-estados-unidos-como-funciona/

12 https://www.eluniversal.com/politica/92038/gobierno-de-joe-biden-otorga-proteccion-temporal-a-los-venezolanos-en-eeuu

13 https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-internacional-55729206

14 https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-13&chapter=4&clang=_en

15 https://actualidad.rt.com/actualidad/385981-crisis-humanitaria-maduro-venezolanos-colombia-eeuu

16 https://elpais.com/internacional/elecciones-usa/2020-10-30/biden-en-florida-a-trump-le-encanta-hablar-pero-no-le-importan-los-cubanos-y-venezolanos.html

17 https://www.france24.com/es/programas/migrantes/20210209-joe-biden-estados-unidos-reforma-migratoria

18 https://forointernacional.colmex.mx/index.php/fi/article/view/2550/2529