Index

Powerful countries are the most targeted

Trafficking and smuggling are not the same

Trafficking as an argument for the criminalization of migrants

Multilateralism against trafficking

From criminalizing victims to criminalizing countries

Instrumentalization of trafficking for other purposes

A day for conscience, not for attack

References

Summary:

- The most powerful countries continue to be the biggest recipients of trafficking, while women, children, migrants and unemployed people are the most affected populations.

- Trafficking is used as an argument for the criminalization of migrants, as well as for the justification of billions of dollars invested in surveillance and spying systems that do not solve the problem, but rather increase it and contribute to other ends.

- It is urgent to heed the call of the United Nations for governments to address immediately and head-on the problem of trafficking in order to save the lives of millions of people affected.

Introduction

On December 18, 2013, during its 68th Session, the General Assembly of the United Nations approved resolution A/RES/68/192, which establishes that, as of 2014, July 30 will be commemorated as the World Day against Trafficking in Persons. The choice corresponds to the fact that three years earlier, precisely on that day in 2010, the UN approved the so-called Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons (64/293).

The purpose is not to celebrate another anniversary of the launching of the United Nations Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons, but to raise awareness about the critical situation of victims of human trafficking, as well as to promote and protect their rights. The issue of human trafficking has received enormous attention in recent years, however, the solutions have not been built, on the contrary, it has been instrumentalized to justify the creation of spying programs, implemented mainly by U.S. administrations, which does not contribute to the solution of the problem and generates a greater criminalization of trafficked persons, exacerbating the root problems that lead to human trafficking.

In recent years, given the huge increase in the global phenomenon of human mobility, it has become imperative to call attention to the commitments that the Member States assumed at the time, since the greatest number of people affected by trafficking are migrants, and in an alarming proportion of them are women and children. In other words, the victims of human trafficking are mainly people from all over the world who flee their countries of origin due to violence caused by armed conflicts and civil wars, or driven by severe economic crises as a result of financial and trade blockades imposed by other countries.

According to the most recent statistics (2020), the number of child victims of trafficking has tripled in the last 15 years and the percentage of children has increased fivefold. These data are contained in a report published in February 2021 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

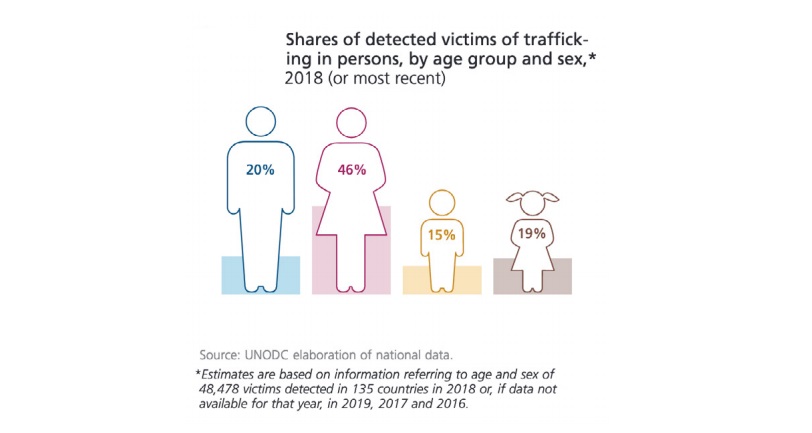

A press release on the United Nations website on this report reveals that, out of every 10 victims detected globally, five are adult women (46% of the total number of victims) and two are girls (19%). Only 20% of the victims are adult men; and the rest, 15%, are boys.

Regarding the forms of exploitation of the victims, girls are mostly trafficked for sexual exploitation, while boys are used for forced labor. In fact, the overall statistics are just as alarming. Fifty percent of the total number of victims are destined for sexual exploitation. While 38% is directed to the forced labor sector and 6% to criminal activity. The rest (another 6%) is destined for organ trafficking, forced marriages, domestic service, sale of infants and other forms of exploitation by criminal groups associated with trafficking.

It also states that in 2018 alone, 148 countries “detected and reported around 50,000 victims of human trafficking.” However, they clarify that given the hidden nature of this crime, the actual number of victims is surely much higher.

Powerful countries are the most targeted

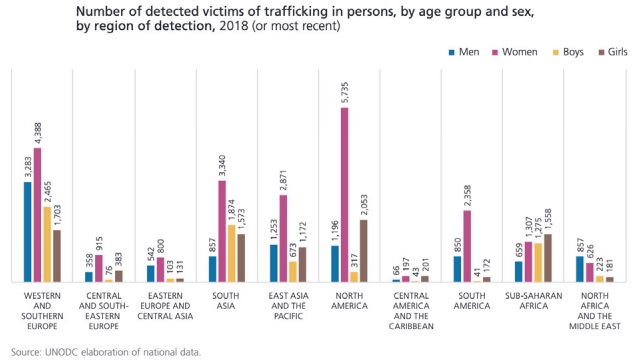

According to the report, the region of the world with the highest number of recorded victims is North America with 5,735 women, 2,053 girls, 1,196 men and 317 boys. It is followed by Western and Southern Europe with 4,388 women, 1,703 girls, 3,283 men and 2,465 boys.

These figures are significant, as they reveal that the countries receiving the human trade continue to be the most powerful nations in the world, which, in addition, receive multiple complaints about the inaction of national authorities in the face of this scourge.

In the case of the United States, according to the IPS news agency, in a report published in August 2019, that nation “is no exception to the practice of modern slavery, even though it is a crime for which it is rarely held accountable at the United Nations and other international bodies.”

According to IPS, a number of veiled crimes persist in the U.S. in urban centers and border towns, including forced labor of migrants, sexual exploitation of minors and domestic servitude, all of which are typifications of human trafficking.

In addition to recalling the high-profile cases of billionaire Jeffrey Edward Epstein, singer R. Kelly, members of British royalty and even U.S. congressmen involved in scandals involving human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, including minors, the same newspaper report also includes statements by human rights lawyer and member of the NGO Equality Now, Romina Canessa, who acknowledges the difficulty of having exact figures on how widespread sex trafficking is in the United States.

“We know that the United States is a source, destination and transit country for trafficking. We also know that the majority of trafficking victims are U.S. citizens and that the most frequent form is sex trafficking of women and girls,” Canessa told IPS.

In the case of Europe, according to a February 2021 European Parliament press release, between 2017 and 2018, European Union countries reported 14,145 victims of human trafficking, 72% of whom were women and girls. According to a report by the European Commission, children accounted for 22% of the total number of registered victims. However, the actual number could be much higher due to the lack of consistent and comparable data.

Similar to what was reported in 2020 by the UODC, in Europe more than half of the registered victims were trafficked for sexual exploitation, while 15% were trafficked for various types of forced labor and 15% were trafficked to other destinations such as begging, organ removal or domestic servitude.

For this reason, in session on February 10, 2021, the MEPs demanded that member countries of the multilateral body tighten anti-trafficking rules and especially criminalize what they called the “conscious use of sexual services”. They also urged the design of stricter child protection measures and improved protection for migrants and asylum seekers, who in their view are at particular risk of falling victim to human traffickers.

These two cases (U.S. and Western Europe), together with the contents of the UNODC report, demonstrate that human traffickers’ prey on the most vulnerable sectors, such as migrants and the unemployed, as well as victims of the economic recession caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has exposed more people to the risk of trafficking.

In this context, UNODC Executive Director Ghada Waly called on UN member countries to design policies and implement measures to protect potential victims of human trafficking.

“Millions of women, children and men around the world are out of work, out of school and without social support in the continuing COVID-19 crisis, leaving them at greater risk of human trafficking. We need targeted action to prevent criminal traffickers from taking advantage of the pandemic to exploit the vulnerable,” he said in a statement on the occasion of the launch of the 2020 report on the issue.

In this regard, it is important to note that such actions, apart from seeking out and punishing traffickers, would have to get to the structural root of the problem, stopping the policies that make the hardest hit social sectors more vulnerable and that lead many people to fall prey to trafficking networks, and resuming or strengthening social protection programs, such as social insurance programs and access to medical services – particularly for mothers and children – in countries such as the United States where a correlation has been seen between the end of such programs (beginning with the Clinton presidency) and the increase in human trafficking.

Likewise, one of the structural causes that can be mentioned has to do with the use of economic coercive policies that lead to the impoverishment, precariousness and vulnerability of society, as is the case with unilateral coercive measures as a weapon of international “soft” warfare, which have contributed to human trafficking in countries that are enemies of the countries that implement them.

Trafficking and smuggling are not the same

Trafficking in persons is often confused with smuggling of migrants. Although they are closely related and both practices constitute crimes punishable under national legislation and international public law, there are differences that should be pointed out. What they do coincide, as we have pointed out above, is that migrants are the potential and most recurrent victims of both criminal activities and those whose fundamental rights are most violated.

For the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), in a material prepared for its University Justice Education Module Series, both smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons are often “overlapping and correlated phenomena that commonly exist on a continuum. That is, in many cases, the former precedes the latter.

Article 3 of the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air defines smuggling of migrants as “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or permanent resident”.

Said protocol criminalizes not only the smuggling of migrants, that is, the facilitation of the illegal entry of migrants into a country for the purpose of obtaining some type of profit, but also related activities, such as allowing the stay of migrants by fraudulent means or producing, obtaining, providing or possessing falsified or illegal documents to enable smuggling.

Trafficking in persons is defined in Article 3 of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.”

As we have noted, the coincidence between the two illegal activities is that migrants are, for the most part, their potential victims. For example, both use the same routes and similar methods of transportation and, in some cases, according to UNODC, are carried out by the same perpetrators. Generally, “persons who are smuggled may also be victims of trafficking or may become victims during or after the smuggling process”.

In fact, migrant smugglers often negotiate with human traffickers, which creates a complexity that must be addressed by both multilateral agencies and national authorities, always safeguarding the fundamental rights of the victims.

Trafficking as an argument for the criminalization of migrants

The situation of vulnerability of trafficked persons manifests itself in various ways. Vulnerability in their countries of origin may be the cause that leads them to voluntarily migrate or to be forced to move to other countries. But it can also be a consequence, i.e., their rights may be violated again as a result of being trafficked.

One of the most significant forms of ex post vulnerability is the criminalization to which they are exposed, a process that leads to further violations of their rights such as forced expulsion, denial of the right to asylum or unjustified imprisonment.

For example, in 2010, Thai authorities arrested and deported 557 undocumented Cambodians from Bangkok. According to a Global Alliance Against Trafficking in Women (GAATW) report published in 2011, “the government had received complaints of people begging in the city. The migrants were charged with illegal entry and gang leaders must face charges of human trafficking. Instead of having the right to claim compensation for forced begging or to file a legal case for abuse or trafficking, the beggars were deported. The three days between their arrest and deportation could not be enough time for immigration officials or NGO representatives to take the testimonies of the 557 individuals and assess whether they were trafficked. Instead of receiving assistance as trafficked persons, the Cambodians were criminalized. Thus, both traffickers and trafficked persons were considered criminals.”

This situation is repeated in areas of intense human mobility such as the southern border of the United States or the central Mediterranean, where, in order to justify expulsions, imprisonment or the denial of the right to asylum, there is a tendency to criminalize migrants and victims of international trafficking.

For UNODC, the solution lies in the timely and effective identification of smuggled and trafficked migrants to break the cycle of vulnerability, encourage cooperation with justice and ultimately progressively eliminate the ability of smugglers and traffickers to act with impunity.

From criminalizing victims to criminalizing countries

Dangerously, we are currently witnessing a new phenomenon associated with human trafficking: the use of this phenomenon as an argument by some States to criminalize the governments of other countries, through inconsistent denunciations.

The purpose is to condemn before international public opinion and within multilateral organizations the alleged commission of the crime of smuggling of migrants or trafficking in persons to nations that do not agree with the political or economic interests of the complainants, almost always powerful countries of the European Union (EU), in the case of displaced persons from North Africa, and the United States of America on Mexico and, more recently, Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

According to a report presented on July 1, 2021, the U.S. State Department stated that Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela “are not making sufficient efforts to prevent human trafficking”. Of course, the information was quickly replicated by international media, news agencies and social networks, fulfilling its objective of giving resonance to a statement coming from the country, precisely, located in the region that leads the world in human trafficking statistics.

The document, released by the Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, indicates that there are countries that not only do not contribute to reduce human trafficking, but, in their biased vision, sponsor it. In addition to Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela, the list is completed by nations such as Afghanistan, Algeria, Myanmar, Comoros, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Iran, North Korea, Malaysia, Russia, South Sudan, Syria and Turkmenistan, according to a note from the Spanish agency EFE.

The same newspaper report replicates Blinken’s remarks about Cuba, pointing to an alleged “government pattern of taking advantage of worker export programs with strong signs of forced labor, particularly in its foreign medical mission program.”

This accusation against Cuba has been harshly criticized in social networks and media around the world, since the Henry Reeve International Contingent of Doctors Specialized in Situations of Disasters and Serious Epidemics carries out a work of solidarity throughout the planet, which since its inception in 2005 has been recognized worldwide, especially during the global pandemic of COVID-19, and for which it has been nominated by several organizations for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The official response of the Cuban government was immediate. “We reject in the strongest terms this defamatory campaign by the U.S. Government, promoted in conjunction with the most reactionary and corrupt sectors of that country, including extremist groups of Cuban origin represented in Congress by figures such as Senators Marco Rubio and Robert Menendez,” the Cuban Foreign Ministry said in a statement.

Likewise, the communiqué issued by the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasizes that the Caribbean country has been recognized worldwide for guaranteeing the fundamental rights of its citizens: “Cuba has a policy of Zero Tolerance to any form of Human Trafficking, and an excellent performance in the prevention, confrontation and protection of victims, a record that is recorded by the United Nations and other international organizations”.

Instrumentalization of trafficking for other purposes

The notion of trafficking has been used alarmingly as a weapon of political attack, diverting attention away from the subjects affected. A multi-corporate group has raised billions of dollars to develop cybersecurity systems in the name of stopping human trafficking, which has ended up being used as a system of surveillance and espionage that violates international law and individual freedoms, as it functions as an enforcement of repressive policies. Companies such as Palantir, a contractor for defense and intelligence agencies, as well as Wall Street giants and NSO Group (Israeli company and creator of the Pegasus software) identify their products as tools in the fight against trafficking.

They also receive legitimization from anti-trafficking groups with ultra-conservative ideologies such as Polaris, funded by the same actors, and even the same groups, to justify the integration of electronic surveillance data on a massive scale (which has been systematically used against laws protecting privacy, to criminalize activists), and the development of spying software that has then been used against politicians, dissidents, human rights activists, journalists and even heads of state who apparently pose a threat to global hegemonic powers.

It is striking that companies allied to governments with a strong repressive and military component invest billions of dollars (from public and private sources) in monitoring and spying systems that, far from stopping human trafficking, have made people, organizations and even countries fighting against the causes of this scourge even more vulnerable.

Multilateralism against trafficking

Achieving a strong and sustained multilateral commitment against human trafficking has been, if not impossible, at least very difficult to achieve. Transnational crime in general and human trafficking in particular constitute a complex reality that involves, in addition to a flagrant violation of human rights, a substantial financial movement estimated at several trillion US dollars per year. This, together with the unintelligible diversity of political and geostrategic interests of nations or economic groups around the world, form an invisible but powerful wall that hinders the achievement of a joint, coordinated and multinational action to combat this scourge that affects millions of people in the world, especially displaced persons in various regions of the planet due to political and economic crises or armed conflicts.

The most evident manifestation of this veiled contention not to assume a firm commitment against human trafficking is the delay or tardiness of the most powerful countries in the processes of ratification, acceptance, approval and accession to the instruments that support the multilateral mechanisms that have been created to combat this international crime.

For example, an important precedent was the 1949 Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others, one of the first efforts of the United Nations, since its creation in 1945, to curb an international reality that was becoming more complex in the post-war period. However, since the entry into force of this instrument, transnational organized crime has devised new and sophisticated ways to traffic mainly women and children.

But it was not until December 2000, 50 years later, when 148 countries met in the city of Palermo, Italy, to sign the new United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. According to the document Guide to the new UN Trafficking Protocol, published in 2006, of the 148 countries present, 121 signed the new Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and only about 80 countries endorsed one of its additional documents: The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, which, together with the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (presented and signed at the same Convention), underpins the strategy of the 2010 United Nations Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons, which is celebrated as World Day against Trafficking in Persons on July 30.

The status of signatures and ratifications of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, as of July 16, 2021, stands at 117 signatories, according to the United Nations website on the status of multilateral treaties.

It should be noted that, between the time of signature (mostly in 2000) and the time of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession (different concepts in the UN system), some of the countries identified as the main recipients of human trafficking and trade took between five and six years to ratify (Germany, 6 years), accept (Netherlands, 5 years) or approve (European Union, 6 years) the Protocol.

Along with some Asian countries, the cases of Germany and the Netherlands are significant, because already in 2006, the resistance of these nations to adhere to a Protocol that affects the economy that has been sustained by the sex trade was warned: “Some governments and a number of NGOs that make a lot of noise and are very well financed, want to separate trafficking from prostitution to avoid the contentious issue of legalization/regulation of prostitution as an economic and labor sector. Countries such as the Netherlands and Germany that have legalized prostitution, abolished anti-pimping laws, and virtually live off the earnings of women in prostitution, have invested heavily in the sex industry. They interpret the abuse or exploitation of women in the sex industry as accidental, not intrinsic to prostitution itself, as if the harm to women were incidental, secondary or the result of the behavior of a pimp or an improper buyer,” states the aforementioned document Guide to the new United Nations Protocol on Trafficking in Persons.

In the case of the United States of America, the country ratified the Protocol in 2005, but with certain reservations that make it clear that its legislation is above the multilateral protocols on the matter, thus demonstrating its rejection of multilateralism as a means of resolving transnational problems.

“The United States of America reserves the right to undertake the obligations under this Protocol in a manner consistent with its fundamental principles of federalism, pursuant to which both federal and state criminal laws must be considered in connection with conduct covered by the Protocol. U.S. federal criminal law, which regulates conduct based on its effect on interstate or foreign commerce or other federal interest, such as the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition of slavery and “involuntary servitude,” serves as the primary legal regime within the United States for combating the conduct contemplated by this Protocol, and is largely effective for this purpose,” reads one of the reservations filed with the United Nations.

The inaction of many nations, as well as the rejection of multilateralism, in defense of a supposed unilateral search for solutions to a problem that, in essence, is transnational, demonstrates the double standards and the evident resistance of some member countries to the insistent calls of the United Nations to adopt a proactive and truly committed attitude to combat human trafficking, from a multilateral perspective and in accordance with public international law.

A day for conscience, not for attack

The latter leads us to emphasize the reason for the commemoration of July 30 as World Day against Trafficking in Persons. As we said at the beginning, the aim is to raise awareness of the situation of victims of human trafficking and to promote and protect their rights, considering the complexity of the issue, the political and economic interests behind it and the real strategies to achieve urgent solutions.

This effort, but also this criticism, has been reflected in the promotional slogans of the last few years in which this date has been commemorated. For example, in 2019, the phrase “Let’s ask our governments to act against human trafficking” was promulgated, in a clear call to States and their governments to act, definitively and without double standards or hidden agendas, to combat this scourge that every day affects more migrants around the world.

References

(14) Palantir official website. Available at: https: //investors.palantir.com/

(15) Polaris official website. Available at: Corporate Partnerships | Polaris (polarisproject.org).