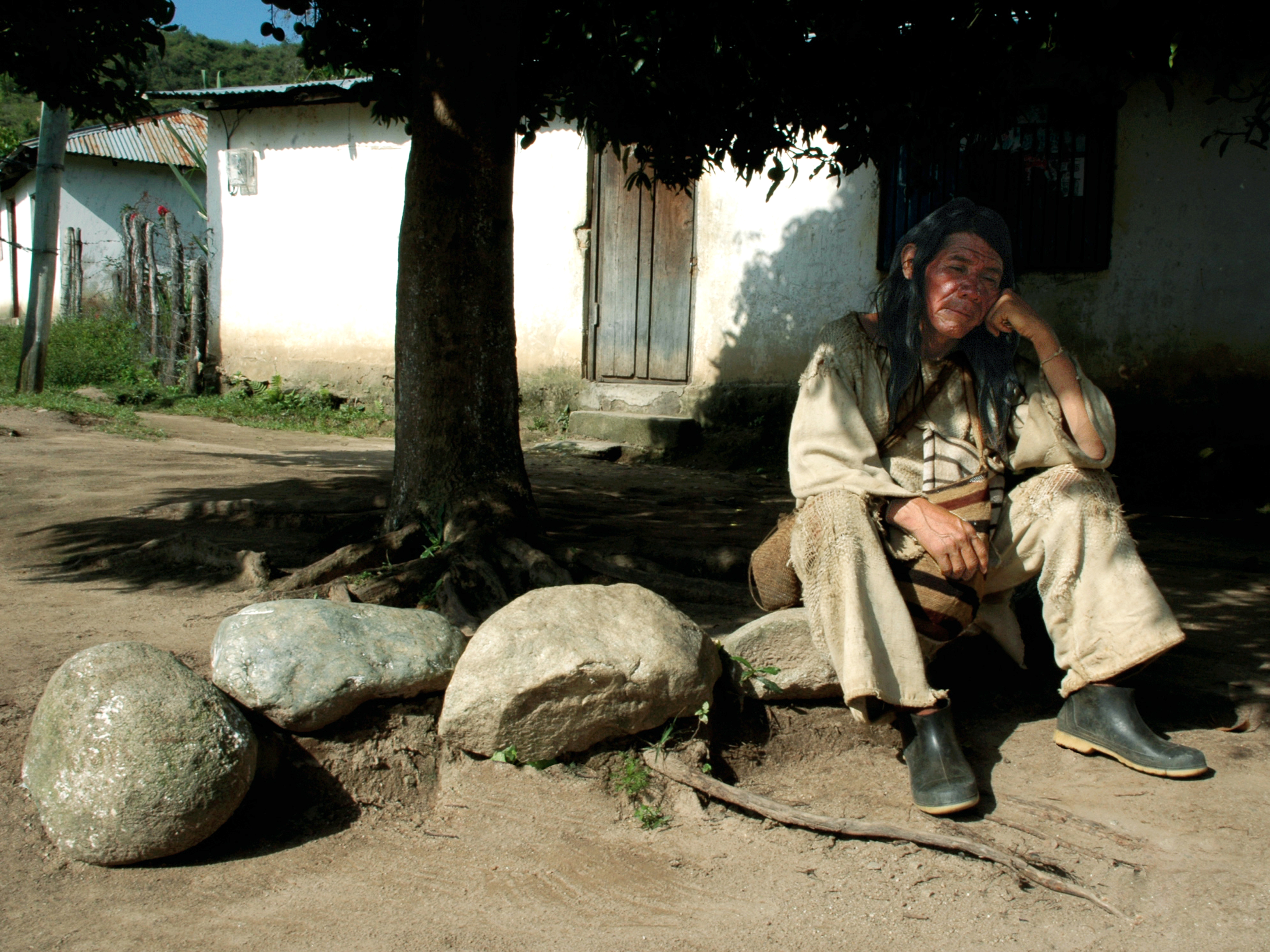

The forced displacement of which the Colombian population has been victim for 50 years, with its origin in the bipartisan violence unleashed after the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán and in the wave of drug trafficking violence and the counterinsurgency war during the 1980s, has had special and very specific connotations on the ethnic groups of that country, such as the Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities1. It is these human groups that have suffered the most from the effects of the cultural and psychosocial tearing apart produced by the process of relocation and deterritorialization left behind by forced migration. At the same time, the loss of territory brought by the Colombian internal conflict has altered different aspects of the life of the communities -economy, cosmovisions and cultural practices-, to which it is inextricably linked because it is a space endowed with a deep symbolic charge and multiple senses that organize reality2.

The phenomenon of forced displacement in Colombia responds to a logic of concentration of agrarian property and territorial control by large landowners, armed groups and organized drug trafficking gangs, as well as to the development of megaprojects linked to investment in large infrastructure works and exploitation of natural resources carried out by national and transnational capital. In the midst of these struggles and alliances between various legal and illegal actors, Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities have been exiled and dispossessed of their ancestral territories, through practices that have led to serious violations of their human rights, marked by massacres, selective killings and people’s forced disappearances.3

According to figures from the Information System on Human Rights and Displacement (Sisdhes), created by the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (Codhes), a total of 32. 217 people were forcibly displaced in Colombia during 2020, being the Colombian Pacific (made up of coastal municipalities of the departments of Cauca, Chocó, Nariño and Valle del Cauca) one of the most affected regions; only in one of the departments that is part of that region, Nariño, the largest number of displacement events was concentrated (30), leaving 11,470 people in this situation. Similarly, more than 50% of the victims of displacement belonged to different ethnic groups, with the Afro-descendant population having the largest number of displaced persons with 9,150, while 7,049 belonged to indigenous peoples.4

The Pacific is one of the regions most affected by the violence of armed groups and the criminal and illegal activities of drug trafficking gangs. Codhes specified, in a bulletin published in November 2017, that for that year this region concentrated 33% of the total of armed actions and breaches of International Humanitarian Law, in direct aggressions against the civilian population by unidentified illegal armed groups, the Public Forces, the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC), the National Liberation Army (ELN) and other dissident guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)5. Likewise, for the same year, the Colombian Pacific concentrated 68% of the massive and multiple displacements occurred nationwide6. According to the organization, this is due to the fact that this area, which gathers most of the titled Afro-descendant and indigenous reservation territories, constitutes the exit corridor for narcotics to other countries and concentrates the largest number of cultivated hectares of coca (Nariño and Cauca).

Recently, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, called on Colombian authorities to take effective measures to protect the population from persistent violence throughout the country, emphasizing the need for the National Commission for Security Guarantees to develop a public policy to dismantle “criminal organizations that have been named as successors to paramilitarism and their support networks, as called for in the 2016 Peace Accord. It also urged authorities to conduct prompt, thorough and impartial investigations into all reported allegations of human rights abuses and violations, and to uphold victims’ rights to justice, compensation and reparations.7

In this regard, researchers in the field argue that one of the causes of the sustainability over time of this internal humanitarian tragedy lies in the weakness of the Colombian state apparatus. According to Ceballos Bedoya, the fragmentation and precariousness of the Colombian State’s institutional framework has been a constant in the nation’s history, a condition that would explain why State authorities are unable to exercise and maintain control over large portions of the national territory. “In a structured and operative State, forced displacement would not cease to be a sporadic, conjunctural event, without the configuration of a human catastrophe of such prolonged duration and uncontainable force as that of the Colombian experience”.8

In the absence of a solid institutional framework and the lack of a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence for the maintenance of internal order, Colombian society finds itself facing a vulnerable State, incapable of providing security and services. Thus, spaces are opening up for the emergence of parastatal dynamics that result in the dispute of different groups for power and are expressed in a generalized atmosphere of violence. According to information from the Instituto de Estudio para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Indepaz), for the period 2018-2019 there were 15 narco-paramilitary groups deployed throughout the Colombian territory with defined actions9 and with close links to the state apparatus. On this point, the non-governmental organization Human Rights Watch has denounced for decades the active coordination between Colombian Army brigades, police detachments, government units and paramilitary groups in the common goal, among others, of combating the guerrillas. In the words of a Colombian municipal official, the relationship between the two actors constitutes “a marriage”.10

In an article published by the National Association of Displaced Afro-Colombians (Afrodes), Marino Córdoba, human rights activist and director of the organization, narrates the events of December 20, 1996 and February 26 and 27, 1997 in the municipality of Rio Sucio, department of Chocó, an episode that went down in history under the name of “Operation Genesis” and which has been one of the bloodiest war actions carried out by paramilitaries and Colombian State institutions against the Afro-Colombian civilian population. There, the Colombian Army and paramilitaries joined forces in a supposed anti-subversive maneuver, establishing themselves in the area, exercising control over the movement of the population and food, improvising clandestine cemeteries and forcing the inhabitants to abandon their territory. Dozens of people were disappeared and killed, others had to flee for their lives. When the communities denounced the facts, “the full weight of the law fell on them, many were murdered and disappeared, others still have judicial processes and the communities have been and are stigmatized as collaborators of the guerrillas or paramilitaries”.11

Faced with this dramatic picture of generalized violence, it is imperative to support the work that different Colombian civil society organizations have been carrying out for decades, aimed at implementing actions to raise awareness among the different sectors of national society regarding the urgent need to protect the Afro and indigenous populations of the country, particularly affected by armed violence. Likewise, to urge Colombian institutions to strengthen their commitment to monitoring and overseeing the State’s obligations to guarantee the protection of the fundamental human rights of the population in situations of forced internal displacement.

References

1 Elsa Rodríguez (2008), “Andean region: population dynamics and public policies – International meeting”, in UNHCR. Available at: https://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/Pueblos_indigenas/palau_2008_indigenas_afrocol_despl.pdf?view=1

2 Luis A. Arias (2011), “Indigenous and Afro-Colombians in situation of displacement in Bogota”, in Portal de revistas Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Available at: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/tsocial/article/download/28365/38859

3 To reverse forced exile: protection and restitution of territories usurped from the displaced population in Colombia (2006), in Colombian Commission of Jurists. Available at: https://www.coljuristas.org/documentos/libros_e_informes/revertir_el_destierro_forzado.pdf

4 Jennifer Gutiérrez & Francy Barbosa (2021), “Displacement in Colombia: What happened in 2020?”, in Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento. Available at: https://codhes.wordpress.com/2021/02/16/desplazamiento-forzado-en-colombia-que-paso-en-2020/

5 y 6 “Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento Codhes”, in Boletín Codhes Informa. Available at: https://codhes.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/boletc3adn-codhes-informa-93.pdf

7 UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (2020), “Bachelet urges Colombia to improve protection amid heightened violence in remote areas”. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26608&LangID=E

8 María A. Ceballos (2013), “Forced displacement in Colombia and its arduous reparation”, in Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, year 15, nº 29. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/51408659.pdf

9 Indepaz (2020), “Report on the presence of armed groups in Colombia. Update 2018 -2019”. Available at: http://www.indepaz.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/INFORME-GRUPOS-ARMADOS-2020-OCTUBRE.pdf

10 Human Right Watch (2001), “The ‘Sixth Division’: Military-paramilitary Ties and U.S. Policy in Colombia”. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/colombia/1.htm

11 Marino Córdoba (2020), “24 años de la operación Génesis, un genocidio que sigue impune en Colombia”, en Afrodes, 23/12/2020. Disponible en: http://www.afrodescolombia.org/operacion-genesis-marino/#more-4306